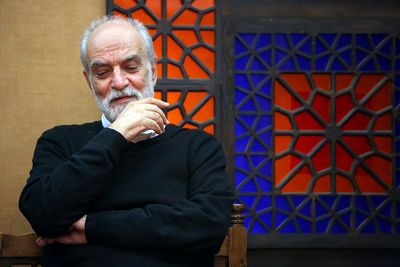

Aydin Aghdashloo (born October 30, 1940) is a painter, graphic designer, writer, and film critic.

As one of the most celebrated artists of Iranian modern and contemporary art, he explains how his works show the thought of gradual death and doom, how he recreates remarkable classic works in modern and surreal forms, how he wants to be remembered as a painter and not artist, and why he holds solo exhibits after many years away from the limelight.

How come we rarely see you hold solo exhibitions?

After the 1973 solo exhibition I started loathing the very idea of it. I have in recent years shown my works in group exhibits though. The only reason I held the 2014 exhibition was to let others know what I had been up to all this time.

Have you changed your mind since?

I don’t know where I stand and who my contemporary audiences are. I have no plans to build new audiences. The ones I have are great and more than enough. When you are in this profession for 40 years, you better be fully prepared for anything. It's something to see my works on the Internet and in books; it’s totally another to look at them in a gallery, in full details, with all their souls and meanings. I got that idea after a solo exhibit in Dubai. That’s when I decided to hold solo exhibitions on a regular basis. This way I can clear out misunderstanding and help fans enjoy the real thing, up close and personal.

You portray different periods in your works. Why is that?

As you know, I never keep my paintings. I sell them. So when an exhibition is upcoming, I start painting again. In my last exhibition I showed 11 works from different eras. Unless you are a Picasso, any painting you draw, even after 50 years, it’s still a continuation of your previous jobs.

How do you prepare collections for an exhibit?

I always try to have at least one sample from each and every period. That includes calligraphy, miniature, memoirs, seventh century earthenware, busts from the Renaissance, and even wooden heads. It has to be a collection in itself. Other works may also come handy, such as a painting of my mother’s face, a painter pulling out an arrow from his chest, and so on. You should always keep an eye on in the commercial aspects of the show as well. You can’t hold an event, then put a note on each and every painting that says ‘not for sale.’

It just doesn’t make sense. It’s what I call ‘reverspective’ (an optical illusion on a 3-dimentional surface where the parts of the picture which seem farthest away are actually physically the nearest). For instance, when the Museum of Contemporary Art decides to show the works of a deceased artist it's 'reverspective.' There might be some exception to the rule, but all my works are for sale.

You are a humanist. You pay conscious tribute to realistic techniques in your paintings. Tell us more.

There’s always been conflicts and struggles within me. As writer and critic, and as someone who always tries to create something, I never like the terms ‘artwork and artist.’ I have always waged war on myself. I create things in solitude, as it comes from within. It’s all about detachment and partiality. Outward looking leads to remoteness. It’s like giving birth to a child. The whole world, the whole being comes together so a mother could have harmony to give birth to a healthy child. At times she might not be at peace with herself. She might yell, scream and be demanding.

I believe that’s how art is similarly created. It comes from the inside. However, when you assess or criticize an artwork, it has to come from the outside. I have had this struggle with me. At times I have become egoistic, stopping a work half done. I have also worn the inside out to judge what I have created. This bothers me a lot. It forces me to have discipline, be mindful and rational when trying to paint something.

Once an artist brought me a painting from Sohrab Sepehri. He had no idea it was genuine or forged, because it had no signature. I looked at it and said it didn’t need any signature, it was by Sepehri. I was astonished and enjoyed the piece. He had given away that painting as a gift. I can never been like him. Perhaps this has something to do with what I’ve been through all this time. My perspective is never outside the framework of what I have grasped, experienced and learned throughout years.

Who has the most influence on you?

Omar Khayyam in an important influence on me. He is a polymath, scholar, mathematician, astronomer, philosopher and poet, indeed one of the most influential thinkers of the Middle Ages. He has been and still is an important influence on me. This has given or offered me distinctive faces in different times. This perspective has travelled 1,000 years and I might have inherited a small portion of it. The final result is, I’m bewildered by the never-ending cycle of life and death all the time. That’s my perspective. It occupies my mind and captivates my soul. Sometimes those around me complain I chatter a lot about death.

Well, how is it possible to look at the cycle and not notice its final chapter that is death? How is it possible to overlook or deny death itself? I can never do it. I always gaze at the cycle, birth and nothingness. Every birth seems sacred and picturesque to me. I never think there is an ugly child out there in the world. An expecting woman is the most beautiful thing God has ever created. That said, I can never close my eyes to the inevitable ending either. Birth heralds my works.

Paintings from the Renaissance (1300-1600) and Safavid eras (1500-1600), or earthenware from the Ilkhanate Era (1256-1335), they all seem like birth to me; a shiny, splendid birth that human beings have given to this world as a gift. Without it the world will be far less evocative, if not empty. When I see birth I create. When I create, when I draw, I’m also rejoicing life.

The question is how one can celebrate birth. My mother used to say after I was born in Rasht, my father got so excited he went on the roof and recited Adhan - call to prayer. This profound memory has stayed with me. I also celebrate birth. I cannot go on the roof and recite Adhan once again. But I can reconstruct that birth. I praise the works of Reza Abbasi, the calligraphy of Mirdamad, and the paintings of Paula Youlo. This is not just a celebration. I convoy and mourn them as well. I’m always there, somewhere between the fine line of celebrating and lamenting. I know it will die one day and I surely let everyone know that. It’s more like an obituary that reports the recent death of a person in a newspaper, typically along with an account of the person's life and information about the upcoming funeral.

Any final words?

When I’m done with a new painting, I celebrate birth. When I tear it up with something sharp, I point to its gradual death and doom. I account my own story, my own life, which is not eternal. I don’t think much about death, for instance, like The Isle of the Dead by Arnold Bocklin which depicts a desolate and rocky islet seen across an expanse of dark water. The tiny islet is dominated by a dense grove of tall, dark cypress trees, associated by long-standing tradition with cemeteries and mourning.

I never celebrate birth in a conventional manner either. For instance, like Gostav Kelimat whose works are marked by the cycle of death and life. His large painting Death and Life, created in 1910, features not a personal death but rather merely an allegorical Grim Reaper who gazes at ‘life’ with a malicious grin. This ‘life’ is comprised of all generations: every age group is represented, from the baby to the grandmother, in this depiction of the never-ending circle of life. True, death may be able to swipe individuals from life, but life itself, humanity as a whole, will always elude his grasp.

Translation by Bobby Naderi